Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Symptoms, Causes & Treatment

What are the symptoms of GERD?

The most common symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) include:

- Heartburn: This is the primary symptom of GERD. It is a burning sensation or discomfort in the chest or upper abdomen, often occurring after meals or when lying down.

- Regurgitation: A sour or bitter taste in the mouth caused by stomach contents (acid, partly digested food) moving back up into the esophagus and mouth.

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia): The feeling of food getting stuck in the throat or chest when swallowing.

- Chronic cough: Acid reflux can irritate the throat and lead to a persistent cough, often worse at night or when lying down.

- Hoarseness or sore throat: Acid reflux can cause irritation and inflammation of the vocal cords, resulting in hoarseness or a sore throat.

- Nausea or vomiting: In some cases, GERD can cause nausea or vomiting, especially when stomach contents are regurgitated.

- Chest pain: The acid reflux can sometimes cause a burning sensation or discomfort in the chest, mimicking the symptoms of a heart attack.

- Dental erosion: The acid from reflux can wear away the enamel of the teeth, leading to dental erosion and increased sensitivity.

- Bad breath (halitosis): The regurgitation of stomach contents can cause bad breath.

- Asthma or wheezing: Acid reflux can irritate the airways and worsen asthma symptoms or cause wheezing.

It’s important to note that not all individuals with GERD experience all of these symptoms, and some may experience only mild or intermittent symptoms. Severe or persistent symptoms should be evaluated by a healthcare professional, as GERD can lead to complications if left untreated, such as esophageal inflammation (esophagitis), strictures (narrowing), or an increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer.

What are the causes of GERD?

There are several potential causes and risk factors that can contribute to the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD):

- Hiatal hernia: A hiatal hernia occurs when a portion of the stomach protrudes through the diaphragm muscle into the chest cavity. This can weaken the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and allow stomach contents to reflux back into the esophagus.

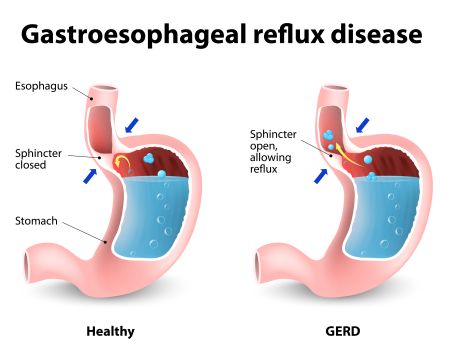

- Lower esophageal sphincter (LES) dysfunction: The LES is a ring of muscle that acts as a valve between the esophagus and stomach. If it doesn’t close properly or relaxes too frequently, stomach contents can reflux back into the esophagus.

- Obesity: Increased abdominal pressure from excess body weight can push stomach contents up into the esophagus.

- Pregnancy: The growing fetus can put pressure on the stomach and reduce LES function, leading to increased reflux during pregnancy.

- Certain foods and beverages: Fatty or fried foods, spicy foods, citrus fruits, tomatoes, coffee, alcohol, and carbonated beverages can relax the LES or delay stomach emptying, contributing to reflux.

- Smoking: Nicotine from smoking can weaken the LES and impair the clearance of acid from the esophagus.

- Certain medications: Some medications, such as certain antibiotics, pain relievers (NSAIDs), sedatives, and blood pressure drugs, can relax the LES or delay stomach emptying, worsening reflux.

- Delayed stomach emptying: Conditions that slow down the emptying of the stomach, such as diabetes or certain neurological disorders, can increase the risk of reflux.

- Dietary habits: Eating large meals, eating too close to bedtime, or lying down shortly after eating can promote reflux.

- Genetics: Some individuals may have a genetic predisposition or variations in genes that control LES function or stomach acid production, increasing their risk of GERD.

In many cases, GERD is a result of a combination of these factors, rather than a single cause. Identifying and addressing the underlying causes or risk factors is essential for effective management and treatment of GERD.

How is GERD treated?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is typically treated with a combination of lifestyle modifications, medications, and in some cases, surgical interventions. The treatment approach depends on the severity of symptoms and the presence of any complications. Here are some common treatment options for GERD:

- Lifestyle and dietary changes:

- A weight loss diet if overweight or obese

- Avoiding trigger foods (spicy, fried, fatty, and acidic foods)

- Quitting smoking and avoiding secondhand smoke

- Avoiding tight clothing that can increase abdominal pressure

- Eating smaller, more frequent meals

- Avoiding lying down for 2-3 hours after meals

- Elevating the head of the bed by 6-8 inches

- Over-the-counter (OTC) medications:

- Antacids (e.g., Tums, Rolaids) can provide temporary relief by neutralizing stomach acid

- H2 blockers (e.g., ranitidine, famotidine) reduce acid production

- Prescription medications:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (e.g., omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole) are the most effective medications for reducing stomach acid production

- Prokinetic agents (e.g., metoclopramide) can help improve stomach emptying

- Surgical interventions:

- Fundoplication (e.g., Nissen fundoplication) is a surgical procedure that reinforces the lower esophageal sphincter and prevents acid reflux

- LINX device – a magnetic ring placed around the esophagus to strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter

- Endoscopic procedures:

- Radiofrequency ablation or cryotherapy can be used to treat precancerous changes (Barrett’s esophagus) caused by chronic GERD

- Endoscopic stitching techniques (e.g., TIF, Esophyx) can tighten the lower esophageal sphincter

- Acid suppression therapy:

- Long-term use of PPIs may be necessary for some patients with severe or persistent GERD

In most cases, treatment begins with lifestyle modifications and over-the-counter medications. If symptoms persist, prescription medications like PPIs may be recommended. For patients who do not respond to medical therapy or have complications, surgical or endoscopic interventions may be considered.

Regular follow-up and monitoring are important to ensure the effectiveness of treatment and to detect and manage any complications or progression of GERD. Early and appropriate treatment can help prevent further damage to the esophagus and improve quality of life.